MSU Graduate Investigates Presence of Monarch Butterflies and Other Pollinators in Roadside Habitats

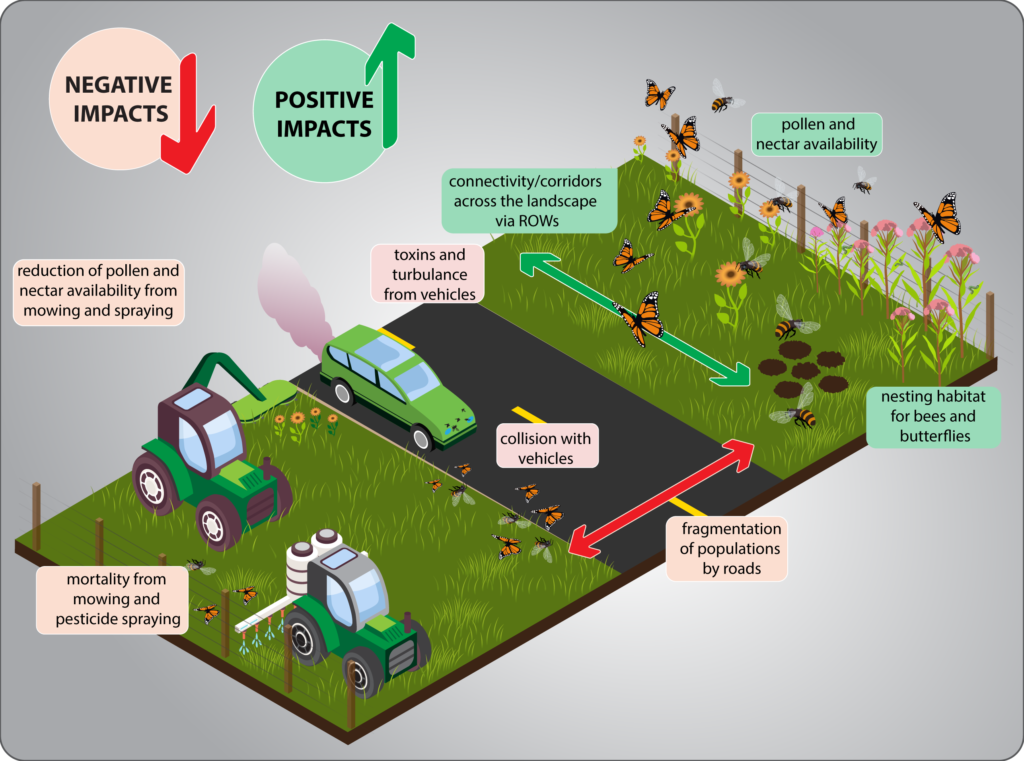

Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus), the striking and iconic orange and black insects of postcards and motivational posters, have been in population decline since the 1980s and Thomas Meinzen, a master’s student in Montana State University’s Ecology Department, turned to a largely overlooked environment to save them. His thesis, Bees and Butterflies in Roadside Habitats: Identifying […]

WTI Employees Share First-Time TRB Experiences

Two of WTI’s newest employees attended their first Transportation Research Board (TRB) conference in January, 2022. We asked them to share their experiences. Jen MacFarlane: This was my first time at TRB and my experience focused on attending sessions and meetings related to public health, walking, bicycling and other physical activity-related content. I was particularly […]

A Note from Our Director: Welcome, 2023!

Hello readers, and welcome to 2023. Like many of you, WTI had a busy January, kicking off the new year at the 2023 Transportation Research Board (TRB) Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. This year’s meeting drew over 11,000 people, including twelve from WTI, two of whom experienced their first TRB and share their reflections of […]

IN THE NEWS: GoGallatin Program Manager on Potential for Ride-Share Partnership, WTI Road Ecology Manager on Benefits of Wildlife Crossings

GoGallatin Program Manager Highlighted in Mass Transit Magazine Earlier this month, WTI Research Associate Matthew Madsen discussed the role of trip planning in a Mass Transit Magazine article about Whitefish, Montana’s plan to reduce transportation emissions. Madsen, who is also the GoGallatin Program Manager, presented to the City on a potential partnership with the trip […]

WTI Schedule for the 2023 TRB Annual Meeting

Many of WTI’s employees will attend the 2023 Transportation Research Board (TRB) Annual Meeting (January 8-12, Washington, D.C.) to participate in an international collaboration and ideas exchange. They will also share their own research and expertise in poster sessions, lectures, and council meetings. “Expected to attract thousands of transportation professionals from around the world, the meeting program covers […]

IN THE NEWS: WTI Road Ecology Program Manager: Montreal Presentation Featured in International News Service

WTI’s Road Ecology Program Manager, Rob Ament, participated in a half-day event, held on the side of the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Global Biodiversity Framework meetings in Montreal, Canada on December 15, 2022. Hosted by the Infrastructure and Nature Coalition at the Nature Positive Pavilion, Rob led off the session devoted to “Nature Positive Infrastructure: […]

WTI Researchers to Teach MSU Course on the Intersection of Transportation & Health

Transportation systems that prioritize motor vehicles have been linked to poor air quality and negative health outcomes such as asthma, may endanger walkers and cyclists, and disproportionately shift the negative effects onto minority and low-income communities. As a new generation of transportation engineers, planners, and policymakers join the workforce, it is important that they understand […]

National Center for Rural Road Safety announces Rural Intelligent Transportation Systems Toolkit

Is your agency looking for innovative solutions to your most common transportation safety challenges? Are you interested in using technology, but not sure which one best fits the needs of your rural area? Or maybe you’ve considered Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) before, but are afraid they are too expensive or only applicable in an […]

MDT Research Newsletter Profiles Three WTI Projects

WTI research is prominently featured in the new issue of Solutions, the research newsletter of the Montana Department of Transportation. Three recently completed projects are profiled in feature articles: “Prefabricated Steel Truss/Bridge Deck Systems.” This study was a WTI and MSU Civil Engineering project led by Damon Fick, Tyler Kuehl, Michael Berry, and Jerry Stephens. […]

Lessons from Highway Wildlife Crossings in a North American Protected Area

Banff National Park and its environs in Alberta, Canada represents one of the best testing sites of innovative wildlife – roadway mitigation passages in the world. Although the major commercial Trans-Canada Highway (TCH) bisects the Park, a diverse range of engineered mitigation measures, including the incorporation of a variety of wildlife underpasses and overpasses have helped maintain large mammal […]