People's Way Partnership

Mission: to build public awareness and support for wildlife crossing structures and associated mitigation measures along U.S. Highway 93 North on the Flathead Indian Reservation and beyond.

US 93 North Wildlife Passages

If you've driven the stretch of U.S. Highway 93 on the Flathead Indian Reservation, you've likely seen the "Animals' Trail", a 197-feet wide vegetated bridge that provides safe passage for wildlife to cross over the busy highway.

Why They Matter

Montana is ranked the second worst in the nation for risk of hitting a deer with an automobile, according to State Farm Insurance.

Do They Work?

After 14 years of on-the-ground monitoring and research... we can definitively state that US 93 North crossing measures have reduced wildlife-vehicle collisions and maintained or improved habitat connectivity for deer and black bear.

US 93 History

Federal, State and Tribal governments agreed to reconstruct US 93 North based no the idea that "the road is a visitor and it should respond to and be respectful of the land the Spirit of the Place."

Read more about: US93 History

Wildlife Passage Research

Wildlife fences and crossing structures benefit human safety and provide safe crossing opportunities for wildlife.

Read more: Research

About-Outreach-Contact

Wildlife fences and crossing structures benefit human safety and provide safe crossing opportunities for wildlife.

Read more:

About Us, Outreach, & Contact

US 93 North Wildlife Passages - Montana

If you’ve driven the stretch of U.S. Highway 93 on the Flathead Indian Reservation, you’ve likely seen the “Animals’ Trail”, a 197-feet wide vegetated bridge that provides safe passage for wildlife to cross over the busy highway.

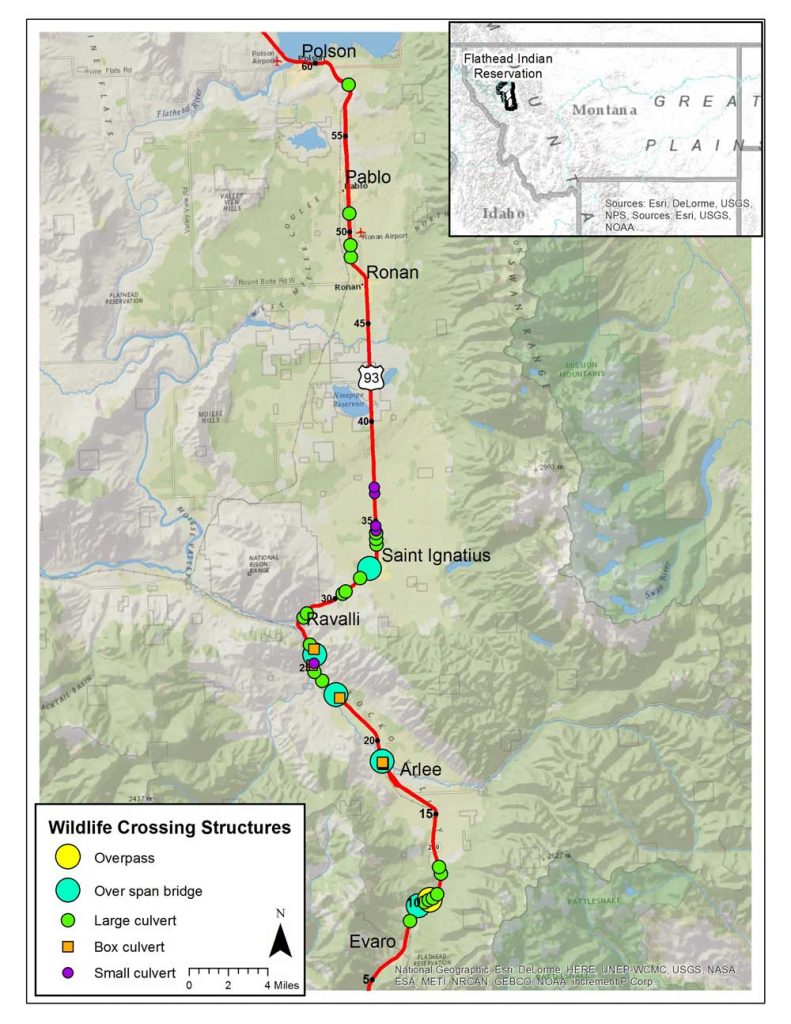

That Animals’ Trail may be the most visible, but it’s just one of dozens of fish and wildlife crossing structures that line the 56-mile stretch of highway.

In total you’ll find:

- 41 fish and wildlife crossings (including the Animals’ Trail)

- 60 jump outs

- 2 underpasses for livestock

- 1 bicycle/pedestrian underpass

- 18 miles of wildlife fencing

- 8.7 miles of road length with wildlife fencing on both sides

The Montana Department of Transportation, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, and Federal Highways Administration constructed these passages to improve safety by reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions and to protect wildlife migration corridors.

The structures are located in areas known for heavy wild life crossings and mortality, and/or locations where the surrounding landscape was best suited for the structures. Typically, you can find them near stream crossings and areas with protected habitat on both sides of the road.

Fish and Wildlife Underpasses:

The culverts and bridges are designed to provide safe crossing opportunities under the highway for wildlife. Structures that include a stream aim to resemble natural stream conditions for fish and other aquatic species.

Wildlife Overpass:

Some large carnivores, deer, elk and moose tend to use vegetated highway overpasses more frequently than wildlife underpasses to access the other side of the road.

Fencing:

Eight-foot high wildlife fencing on both sides of the road keeps wildlife from entering the highway and directs them to crossing structures.

Jump Outs:

Jump outs allow wildlife to safely jump down to the other side of the fence should they be caught in the fenced road corridor.

Wildlife Crossing Guards:

Modeled after cattle guards, wildlife guards discourage deer and other hoofed mammals from entering the fenced road corridor at access roads.

You can find dimensions of each of the wildlife crossing structures in this table. Part of the success of wildlife crossing structures comes from animals feeling secure in approaching or crossing the structures. We appreciate your interest, but please do not approach or enter the wildlife crossing structures; it is not allowed.

The following table details the types and dimensions of the underpasses on US 93 North.

| Type | Size in Feet | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Cement culvert | 10 x 14 | 1 |

| Concrete box culvert | 5 x 7 | 3 |

| Concrete box culvert | 6 x 4 | 5 |

| Concrete footers/divided lanes | 12 x 22 | 1 |

| Conspan arches | 9 x 28 | 2 |

| Conspan arches northbound and southbound | 14 x 43 | 1 |

| Corrugated metal arch culvert | 12 x 24 | 1 |

| Corrugated metal arch culvert | 12 x 22 | 2 |

| Corrugated metal arch culvert | 17 x 24 | 4 |

| Corrugated metal arch culvert | 24 x 13 | 2 |

| Corrugated metal arch culvert | 24 x 15.5 | 2 |

| Corrugated metal arch culvert | 6 x 4 | 1 |

| Corrugated metal arch culvert | 8 x 8 | 1 |

| Corrugated metal pipe or concrete box culvert | 7×5 | 1 |

| Corrugated metal pipe or concrete box culvert | 12 x 22 | 7 |

| Multi span bridge (existing) | – | 1 |

| Open span bridge | 15 x 395 | 10 |

| Open span bridge | 10 x 100 | 1 |

| Open span bridge | 12 x 100 | 1 |

| Open span bridge | 16 x 131 | 1 |

| Plastic coated corrugated metal culvert | 6 x 4 | 2 |

| Wildlife overpass | 49 x 197 | 1 |

Why They Matter

Roads are excellent for connecting people and goods to their destinations, but they can be harmful or even deadly to both humans and wildlife.

- Montana ranked no. 2 in the nation for wildlife vehicle collisions, according to a 2016 study by State Farm Insurance, with Montanans hitting deer about 13,300 times a year.

- In the United States, wildlife vehicle collisions were estimated to cause 211 human fatalities, 29,000 human injuries, and over $1 billion in property damage annually.

- The total number of large mammal vehicle collisions has been estimated at one to two million in the United States and at 45,000 in Canada annually.

- From 1990 to 2004, the number of wildlife vehicle collisions in the US increased 50% while the total number of crashes has remained more or less the same. This means that wildlife vehicle collisions have not only become more common, but they also represent a growing percentage of all collisions that occur.

Both humans and wildlife deserve to safely move between destinations. For animals, the degree to which the landscape facilitates or impedes movement is called wildlife connectivity.

Reduced connectivity in the landscape is the result of habitat fragmentation. Roads contribute to habitat fragmentation when animals become reluctant to cross highways or when animals are killed trying to cross. The degree of aversion to roads may vary by species, age group, and gender but the causes are similar: dangerous and unsuitable habitat due to road width, high vehicle volume, and high vehicle speed.

Road mortality and habitat fragmentation not only affect individual animals, but they can also impact species on the population level, causing a serious reduction in survival probability.

- Animals need to move freely between different types of habitat to find food and water, establish territory, reproduce, and migrate.

- Connectivity allows wildlife to repopulate areas or populate new habitat. This reduces the likelihood that a species disappears from a region and minimizes the potential for inbreeding.

Wildlife fences, in combination with wildlife crossing structures, are an effective solution to these problems. They increase wildlife connectivity, save taxpayer dollars, and reduce deaths and injuries to both humans and wildlife.

Do They Work?

If we want to know whether wildlife-crossing structures work, it’s important to define what success looks like. For the coalition of engineers, scientists, and government officials involved in the renovation of US 93 North, success was centered around two things:

- Reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions

- Maintaining habitat connectivity for wildlife

After 14 years of on-the-ground monitoring and research before, during, and after construction of wildlife crossing structures, we can definitively state that US 93 North crossing measures have reduced wildlife-vehicle collisions and maintained or improved habitat connectivity for deer and black bear.

Our research was concentrated in three main study areas as well as three adjacent road sections that had no wildlife crossing structures (the “control” sections).

Reducing human and wildlife traffic crashes

The number of deer using wildlife crossing structures in the three main study areas versus walking across the pavement averaged 6,293 per year; for black bear that number was 305 crossings per year. Diverting animals away from the road surface means fewer potential wildlife-related car accidents, injuries, or deaths.

Wildlife fences are effective in reducing collisions with large mammals, but their effectiveness depends on the length of the fencing and associated measures.

In the three main study areas where wildlife fencing was implemented, there was a 70-80% reduction in wildlife-vehicle collisions. Interestingly, the number of wildlife-vehicle collisions significantly increased in the nearby unfenced (control) areas.

Although wider lanes and shoulders, longer sight distances, and more gentle curves make rural highways like US 93 North safer in general, our research suggests that without the implementation of wildlife mitigation measures like fencing and crossing structures, the number of wildlife-vehicle collisions will be greater than before highway improvements were made.

Maintaining habitat connectivity for wildlife

The wildlife cameras recorded 22,648 successful animal crossings per year in the 29 crossing structures that were monitored.

Twenty different species of medium-sized or large-sized terrestrial wild mammals used the crossing structures successfully. Most of the crossings were by white-tailed deer (69%). Mule deer and domestic dogs and cats each represented about 5% of the successful crossings. Black bear represented 1.6%.

While the number of black bear crossings was similar both before and after the structures were implemented, more deer use the crossing structures than had previously crossed the highway at grade.

Interested in more statistics, charts, and analyses? You’ll find them in the report (PDF).

US 93 Wildlife Crossing History

Adding Lanes Won’t Solve the Problem

Expanding the highway wouldn’t just add lanes, tribal members pointed out, it would also encourage higher speeds. And higher speeds would increase the number of animals killed by speeding traffic — a safety issue for wildlife and motorists alike.

Wildlife and the places they feed, mate, give birth, and travel hold considerable meaning for the Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d’Oreille people. Tribal biologist Dale Becker was quoted in Sierra magazine saying, “Big-game species provide important subsistence for a lot of families. And the grizzly bear and gray wolf are revered as part of our culture.”

The CSKT also voiced concern that a four-lane highway would literally bisect communities, increase land development and population growth in the area, and negatively affect natural and recreational resources.

Both MDT and CSKT agreed that safety issues needed to be addressed, but the size and configuration of the highway reconstruction and the associated impacts continued to be sticking points. The expansion project stalled for a decade.

A Radical Approach: Spirit of Place

In March 2000, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), MDT, and CSKT met and established a tri-governmental team to reach an agreement. From that process came a radical idea: instead of focusing on how the road will impact the land, focus on how the land should shape the road. The team called this approach a “Spirit of Place.”

The Spirit of Place constitutes more than just the road, it takes into account the surrounding mountains, plains, hills, forests, valleys, and sky. It includes the paths of waters, glaciers, winds, plants, animals, and native people — the whole continuum of what is seen, touched, felt, and traveled through. The design of the roadway would be premised on the idea that the road is a visitor and should respond to and respect the Spirit of Place.

The design team, which included landscape architecture firm Jones & Jones, spent significant time exploring the land, talking to tribal leaders, and performing analyses. They determined that the Spirit of Place approach allowed for many benefits, some of which included:

- Replacing old straight-aways with soft and continuous transition curves to naturally increase spacing between vehicles and eliminate traffic line-ups.

- Adding intermittently spaced passing lanes that would not only reduce construction and environmental costs by minimizing the highway’s footprint, but would also make most of the road realignments possible without altering the existing right-of-way.

- Posting signage that recognized the unique and diverse nature of the surrounding communities.

The Spirit of Place design proposal also included protection and restoration of native plants, water channel restoration, and the most innovative element of the proposal: wildlife crossing structures.

The tri-governmental team signed off on the plan in December 2000 and construction commenced in 2004. The Spirit of Place design was later awarded the President’s Transportation Award for the Environment (American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials) and the Strive for Excellence Team Award (Federal Highway Administration).

Wildlife Passage Research

- Collection of the number of animal-vehicle collisions through Montana Highway Patrol crash reports, Montana Department of Transportation (MDT) carcass removal reports, and bear road mortality data from natural resource management agencies.

- Digital motion-sensitive wildlife cameras at the majority of crossing structures, wildlife guards (similar to cattle guards), ends of fences, and jump-outs

- Sand tracking beds at jump-outs and selected crossing structures

- Deer pellet group surveys to measure potential changes in the deer population size

Other Research on US Hwy 93 North

Research on US93 North wildlife crossing structures has been completed by several graduate students:

A.Z. Andis, M.P. Huijser and L. Broberg. Accepted. Performance of Arch-style Road Crossing Structures from Relative Movement Rates of Large Mammals. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. (Article link coming soon)

Wildlife Connectivity Research (National and International)

Crossing Structures Save Lives and Money

The following research papers and websites provide data on various wildlife connectivity and road safety strategies used in Montana, the United States, and the world. They offer communities, educational institutions, and government agencies the opportunity to learn best practices on how to save lives, reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions, improve habitat connectivity, and be cost-effective. {slider title=”Human Safety and Reducing Wildlife-Vehicle Collisions” open=”false” class=”icon”} Wildlife-Vehicle Collision and Crossing Mitigation Measures: A Toolbox for the Montana Department of Transportation 4Mb Animal-Vehicle Collision Data Collection; A Synthesis of Highway Practice, 2011 (PDF) Wildlife-vehicle Collision Reduction Study; Report to Congress, 2008 (PDF) Effectiveness of Short sections of Wildlife Fencing and Crossing Structures along Highways in Reducing Wildlife–Vehicle Collisions and Providing Safe Crossing Opportunities for Large Mammals. Biological Conservation, 2016 US 93 North post-construction wildlife vehicle collision and wildlife crossing monitoring on the Flathead Indian Reservation between Evaro and Polson, Phase II Final Report, Montana, 2016 (PDF) {slider title=”Habitat Connectivity for Wildlife” class=”icon”} Banff Wildlife Crossings Project: Integrating Science and Education in Restoring Population Connectivity Across Transportation Corridors, 2009 (PDF) 15 Years of Banff Research: What we’ve learned and why it’s important beyond the park boundary, 2011 (PDF) Ten Quick Facts about Highway Wildlife Crossings in Banff National Park, 2012 (PDF) Effects of Highways on Fragmentation of Small Mammal Populations and Modifications of Crossing Structures (Culverts) to Mitigate Such Impacts, Biological Conservation, 2016 Wildlife Crossings Toolkit (US Forest Service and National Park Service) Corridors and Landscape Connectivity: Clarifying the Terminology, May 2009 (PDF) Effects of Roads and Traffic on Wildlife Populations and Landscape Function, Ecology and Society Journal 2011 Wildlife Habitat Connectivity Across European Highways, 2002 (PDF) Effectiveness of Short sections of Wildlife Fencing and Crossing Structures along Highways in Reducing Wildlife–Vehicle Collisions and Providing Safe Crossing Opportunities for Large Mammals. Biological Conservation, 2016. US 93 North post-construction wildlife-vehicle collision and wildlife crossing monitoring on the Flathead Indian Reservation between Evaro and Polson, Montana, Phase II Final Report, 2016 (PDF) Handbook for Design and Evaluation of Wildlife Crossing Structures in North America, 2011 (PDF) {slider title=”Economic Benefits” class=”icon”} Cost Benefit Analyses of Mitigation Measures Aimed at Reducing Collisions with Large Ungulates in the United States and Canada: a Decision Support Tool, 2009 (PDF) {/sliders}About Us, Outreach & Contact

The mission of the People’s Way Partnership is to build public awareness and support for wildlife crossing structures and associated mitigation measures along U.S. Highway 93 North on the Flathead Indian Reservation and beyond.

We do this by providing education and research on the conservation, safety, and economic benefits that wildlife fences and crossing structures offer people and wildlife. We believe that a more informed public will lead to increased citizen, institutional, and governmental support for sustainable highway practices throughout the West, the United States, and other parts of the world.

The People’s Way Partnership is a unique partnership between:

Outreach

Whisper Camel-Means, MS, is a wildlife biologist for the CKST Tribal Wildlife Management Program. She is one of the lead CSKT biologists for US 93 North wildlife crossing project and provides educational field tours of the area.

Student Art Contest: The People’s Way Partnership conducted the Safe Passages for Wildlife poster contest to teach school-age children about the importance of wildlife crossing structures under and over highways for both human and wildlife safety. Find out more about the Wildlife crossing poster competition.

Marcel Huijser, PhD, is the principal investigator for the Post-Construction Monitoring and Research program and gives scientific and educational lectures on the project. He is a research ecologist with Western Transportation Institute – Montana State University.